When will inflation return?

As policymakers embark on an even more aggressive quest to loosen financial conditions and inject record amounts of liquidity to counteract the effects of the pandemic, will investors see inflation return in the near term?

Do the global pandemic and policy response pose higher risks for inflation?

Do the global pandemic and policy response pose higher risks for inflation?

Predictions about rising inflation have begun to sound like the story of the boy who cried wolf. It confounded predictions when inflationary pressures failed to materialize after the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) despite zero or negative interest rates and massive quantitative easing by global central banks. As policymakers embark on an even more aggressive quest to loosen financial conditions and inject record amounts of liquidity into their respective economies to counteract the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, investors find themselves asking the same sets of questions again: Will inflation finally materialize this time around? If so, when? Investors are asking if they should consider a hedge against inflation as part of the overall portfolio, and if so, how?

The very high inflation that persisted for much of the 1970s and 1980s appears to be all but a distant memory. Indeed, in the period since the GFC, the average rate of inflation has been approximately 1.7% in the US and 1.4% in the Eurozone1, meaningfully below the targets set by their central banks. This undershoot has happened even though the Fed’s balance sheet quadrupled and the ECB’s more than doubled in the ensuing ten-year period. Many explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. These include secular factors such as the ageing population, globalization and technological advancements that have suppressed supply chain-induced inflation. In addition, cyclical effects including reduced lending on the part of commercial banks into the real economy that have resulted in diminished aggregate demand for goods and services, declining labor income share of GDP and related rising inequality. Whatever the reasons are, high inflation has simply not materialized.

But what will happen in the future and especially after COVID-19?

But what will happen in the future and especially after COVID-19?

Will the post COVID-19 period be different? Admittedly, the short-term effects of the pandemic are likely to be disinflationary as a result of a large output gap in the aftermath of the worst contraction in recent history. Over the medium- to long-term horizon however, the risk of inflation cannot be ignored as the pandemic has also caused major supply disruptions.

In an effort to support the economy, the magnitude of fiscal stimulus and the pace of central bank intervention has been unprecedented, estimated to be USD 12 trillion2 by year end, and could potentially have inflationary consequences. Indeed, M2, a broad measure of money supply which includes cash, checking and savings deposits and money market securities, has jumped over 20% from the end of 2019 through September of this year3, by far the largest such jump since at least 1981. While the mere increase in M2 alone is not a precursor for future inflation, a catalyst in the form of increased lending by banks who are currently hoarding cash, could result in upward pressure on the prices of goods and services. In addition, private sector savings soared as a result of reduced spending and generous income support from the governments, which could be converted into enormous spending once the virus is under control and confidence returns. This contrasts with income losses and profit declines associated with a typical recession.

Additionally, unlike the GFC when money supply was used to stabilize the financial system (banks), the current aim of policymakers is not to target the banks – who are in large part well capitalized – but rather the real economy. For instance, central banks create money through asset purchases to finance government spending, wage subsidies and bank lending – actions that are more likely to result in a situation where more money chases fewer goods – a textbook definition of inflation.

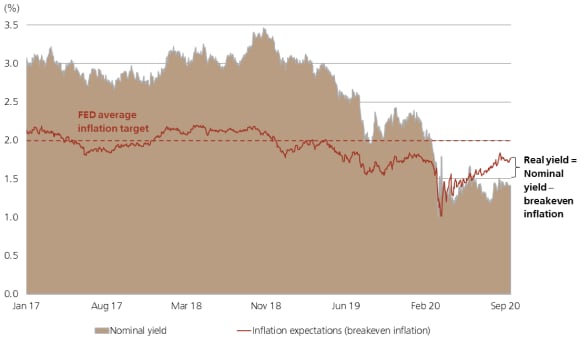

Further, the Fed recently modified its inflation targeting regime from an absolute to an average inflation targeting basis, which would allow future inflation to rise above the 2% target without a threat of raising interest rates, given the significant undershoot over the past 10 years. While this may not necessarily stoke near term increases in the prices of goods and services, the ramifications of these policy actions could likely be felt a few years down the line.

Finally, another major risk for higher inflation is the prospect for governments to run large budget deficits even well after the economy has recovered the lost ground. Central bank bond purchases could suppress yields and crowd out private investors.

Near-term drivers of deflation

Near-term drivers of deflation

The possibility of medium-to-long term inflation has increased based on some of the trends outlined above. However, we acknowledge that low inflation could remain at least for the next year or so. This could be because structural changes to working practices such as recent trends in remote working, technology and automation, lead to disinflationary pressures. Secondly, the absence of a credible vaccine against COVID-19 could keep economies running with meaningful output gaps and thereby limiting their ability to generate inflation, despite massive amounts of stimulus. Finally, the failure of policymakers to induce higher bank lending into the main economy could mean that the increase in money supply from fiscal stimulus may never translate into higher circulation.

How can investors protect against the erosion of purchasing power caused by inflation?

How can investors protect against the erosion of purchasing power caused by inflation?

One of the benefits of the current subdued inflation expectations is the associated low cost of buying protection against future inflation. In that regard, we view inflation-linked bonds as an effective instrument in helping clients protect their portfolios against the erosion of their purchasing power through inflation. This instrument, unlike its nominal counterpart, aims to protect the holder against the effects of unexpected high inflation by paying income and adjusting the principal based on official headline inflation.

Price returns of inflation-linked securities are driven by supply and demand dynamics arising from changes in real rates as well as expectations for future inflation, also known as breakeven inflation (bond yields and prices are inversely correlated).

UBS-AM’s approach to investing in inflation-linked bonds

UBS-AM’s approach to investing in inflation-linked bonds

Example: Relationship between 30-year TIPS and nominal bonds

Key facts

Bloomberg Barclays Global Inflation-Linked Index, as at 30 September 2020

- Market value: USD 3.2 trillion

- Duration: 12.74 years

- Average rating: AA

- Largest Issuers: US (38.88%) and UK (32.31%)

When picking inflation linked bonds or any other investment, it is important to do your homework. Only central banks with a credible history of achieving or nearing their respective inflation targets are suitable candidates for investors to trust these targets. Within developed markets the Fed and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) are two such banks. As noted earlier, the former has recently enacted a policy that is likely to result in a hot-running economy and upward inflationary pressure, ideal conditions for these inflation-linked securities to perform well. The latter continues to oversee an economy with one of the highest real rates in the developed world and has demonstrated a commitment to pushing real yields lower, which could benefit these bonds.

Our strategy offerings that can help you protect your portfolio against inflation

Our strategy offerings that can help you protect your portfolio against inflation

Our suite of solutions range from "go anywhere" total return strategies to benchmark-aware strategies with varying allocations to inflation-linked bonds. One of the most appealing aspects of our solutions is their ability to not just offer exposure to inflation-linked bonds but also to pull on a number of other levers such as credit, FX and rates aiming to generate additional diversified returns regardless of the future path of inflation. When inflation-linked markets look unattractive, or better yet, when there are more attractive opportunities available, our flexible mandate allows us to invest opportunistically in off-index fixed income instruments, subject to guideline limits and risk management.

Characteristics | Characteristics | Total return | Total return | Flexible | Flexible | Global Inflation linked (IL) | Global Inflation linked (IL) | Indexed | Indexed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Characteristics | Strategy | Total return | Global Dynamic | Flexible | Global, EUR, short term (1-3-year) | Global Inflation linked (IL) | Global inflation linked | Indexed | Global, regional |

Characteristics | Investment style | Total return | Benchmark agnostic, investing across all FI asset classes | Flexible | Benchmark aware, able to invest off benchmark across all FI asset classes | Global Inflation linked (IL) | Flexible, global IL strategy. Can invest 1/3 off benchmark across FI asset classes | Indexed | Replicating benchmark risk and return characteristics |

Characteristics | Tracking error | Total return | 4-6% volatility (abs) | Flexible | 200-300 bps | Global Inflation linked (IL) | 300 bps | Indexed | 50 bps |

Characteristics | Alpha target | Total return | Maximise total return | Flexible | 100 - 150 bps | Global Inflation linked (IL) | 75 bps | Indexed | n/a |

Characteristics | Current allocation to inflation-linked bonds | Total return | 19.73% | Flexible | Global: 12.31% | Global Inflation linked (IL) | 70.03% | Indexed | n/a |

Characteristics | AuM (USD, m) | Total return | 1,108 | Flexible | 664 | Global Inflation linked (IL) | 183 | Indexed | 5,651 |

Make an inquiry

Fill in an inquiry form and leave your details – we’ll be back in touch.

Introducing our leadership team

Meet the members of the team responsible for UBS Asset Management’s strategic direction.