Dollar diffusion: China’s opportunity to balance the power dynamics in global finance

With the dollar’s dominance and influence in global finance waning, Barry Gill explores the reserve currency alternatives and investment implications.

Transformational change rarely happens the way you expect. As the American futurist Buckminster Fuller put it, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

Take the dollar’s dominance. With the proverbial ink barely dried on the quantitative-easing printing presses following the global financial crisis, whispers of the erosion of the US’s “exorbitant privilege” were quick to surface. Talk of a multi-polar geopolitical world, with a basket of reserve currencies serving as monetary ballast, has swirled ever since.

Yet we appear no closer to a transition. Old habits die hard, and weaning global finance off its dollar addiction (i.e., de-dollarization) has proved tricky. But look a little deeper and some interesting trends emerge. Perhaps the threat to the dollar comes not from other fiat currencies, but from entirely new ways of doing things.

Lessons from the past

Lessons from the past

The US dollar has been unrivalled as the world’s leading reserve currency since the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1946. Few investors can remember that far back. But before the dollar, the British pound was the main global reserve. Sterling’s rise to supremacy came as the British Empire reached its zenith and lingered until its dying days. Earlier, the Dutch guilder fulfilled a similar global role, again in line with imperial power and economic clout. And before that, it was the Spanish real.

So although it may be difficult to conceive of the death of a global reserve currency, similar shifts have happened in the past. Ray Dalio, the investor and author, argues that the relative decline of US power and the rise of China indicate that just such a shift is underway – on past precedent, at least.1 But as Mr Dalio has also said, “He who lives by the crystal ball will eat shattered glass.”2

The fragmentation of financial architecture

There is no guarantee that the dollar will be toppled in quite the same way that other dominant reserve currencies were. Despite the size of the Chinese economy and China’s leadership in global trade volumes, the yuan is not eclipsing the dollar as the dollar eclipsed sterling in the first half of the twentieth century.

But this doesn’t mean that the dollar is unchallenged. Heightened geopolitical tensions have led to the weaponization of finance, which is now the sanction of first resort for the White House. Witness the US response to the invasion of Ukraine, with the freezing of Russia’s dollar reserves and its exclusion from the SWIFT settlement system. The US currently has 17 other countries or regions under financial sanctions.3

So, as geopolitical tensions increase, many nations have an interest in ensuring that they are not fully exposed to the US financial arsenal. China is foremost among them. Tensions over trade, technology have resulted in an increasingly strained relationship between the world’s two largest powers. This gives China ample incentive to avoid the potential impact of US financial sanctions.

Dethroning the dollar is the obvious way to achieve this. But the Chinese yuan currently accounts for less than 3% of global reserves compared with almost 60% for the dollar.4Still, were foreign reserves to be spread more evenly across a basket of different currencies, the dollar’s standing would be diminished. In a multipolar world, other currencies, including the yuan and even a mooted BRICS currency, would assume more prominent positions – reflecting the decline of US hegemony. Recently, China has been expanding its cross-border interbank payment system, which allows yuan-denominated transactions to be carried out without recourse to Western systems – providing potential for sanction-proof trade.

Against that, the dollar’s position is bolstered by a sizeable incumbency effect and the advantages that the US enjoys over China: a transparent court system, respect for foreign investors’ rights, and deep and open capital market.

Yet the threat to the dollar might come from a different direction. A reserve currency needs to provide investors with three things: a store of value; a unit of account; and a convenient means of payment.

Assessed as a store of value, the dollar is hardly unassailable.5But despite quantitative easing, it has proved more stable over the long term than many other fiat currencies, including the yuan.6The same stability makes the dollar a reliable unit of account for valuing goods and services. However, the dollar’s convenience as a means of payment is already being challenged.

Shifting patterns of payment

In much of the world, cash is no longer king. Take China, where smartphone apps such as Alipay and WeChat Pay have long been used to buy everything from flight tickets to street food. Rather than an expensive electronic payment device, vendors require only a printed QR code.7,8 The COVID pandemic, with its attendant anxieties about hygiene, has accelerated the shift to a cashless society, and it has been echoed in other emerging markets.9While the West continues to rely on cumbersome card networks, much of the developing world is accustomed to simpler, sleeker and more seamless payments.

These digital payment systems have implications for improving cross-border trade by cutting out intermediaries and thus reducing costs. Already, India and Singapore have linked their digital payment systems, as have Singapore and Thailand. Meanwhile, China’s UnionPay, Alipay and WeChat Pay apps are in use in a growing number of developing countries, where their QR-code model makes them cheap and efficient to use.

The creep of crypto

Another potential threat to the dollar’s dominance comes from cryptocurrencies. These offer a decentralized means of exchange outside of government influence.

Crypto provides unit of account and a means of payment, so it offers at least two of the three functions of a reserve currency. There is still disagreement, however, as to its efficacy as a store of value. Its dramatic volatility and high-profile scandals at key exchanges have called this into question.

But Nik Bhatia, an academic, strategist and prominent crypto exponent, says that fiat currency is the uncertain store of value, given its repeated erosion by governments, whether through coin clipping, metal debasement or quantitative easing: “Throughout the ages, currencies have ceased to exist because of one rudimentary fact: governments are unable to resist the temptation to create free money for themselves.”

Throughout the ages, currencies have ceased to exist because of one rudimentary fact: governments are unable to resist the temptation to create free money for themselves.

Bhatia argues that bitcoin’s decentralized nature and political neutrality will eventually make it the world’s leading reserve currency – although he doesn’t expect this to happen anytime soon.

Still, both the Central African Republic and El Salvador have made bitcoin an official currency. El Salvador has gone further by keeping some of its reserves in bitcoin.10 And even if crypto falls short of some claims, it can still help to chip away at the dollar’s dominance.

Central banks go digital

One form of digital currency has more immediate potential to dislodge the dollar. This is central-bank digital currency (CBDC).

The crucial point about CBDCs is that they are legal tender – direct liabilities of the central banks. Unlike digital payments made through bank transfers, credit cards or mobile apps, payments made in CBDCs do not involve intermediaries. That makes them cheaper and quicker – giving them an immediate advantage over traditional fiat currency.

Although Finland had an abortive experiment with CBDCs in the 1990s, China is the leader here. The People’s Bank of China began work on its digital currency almost a decade ago, and real-world testing of the digital yuan got underway in 2020.

This first-mover advantage may allow China to internationalize the digital yuan throughout its vast trade network, which it has bolstered through its Belt and Road initiative. China has already transacted some international trade in yuan, and the digital yuan, with its advantages in speed and cost, may play well with countries happy to see US influence curbed.

However, the digital yuan’s role may still be limited. The People’s Bank of China can set constraints on its use, which may prove unwelcome. There may also be concerns over the monitoring of transactions by China. And China itself may be reluctant to engage in the opening of its capital account that full competition with the dollar would require.

We are in new territory here, with China a pioneer. As other central banks assess the potential for CBCDs of their own, the digital yuan could be the start of something that ultimately renders our existing model of reserve currency obsolete.

Investment implications

There are many ways to interpret all this and translate it into investment decisions. Below are some thought-provoking charts and brief observations.

Chart 1: China sovereign bonds could add diversification benefits

With low inflation and a still-solid GDP growth rate, China has been loosening its monetary policy even as central banks in the West keep theirs tight. The distinct economic trajectories of China and most of the world’s developed nations mean that their bonds are increasingly uncorrelated too.

As the chart above illustrates, the historical correlation between US and UK sovereign bonds and their Chinese counterparts has broken down significantly over the last 10 years, making Chinese bonds a potentially attractive diversifier for portfolios.

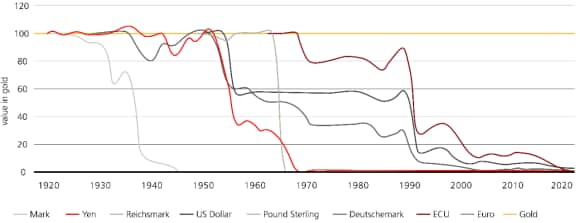

Chart 2: The advantages of gold

A common claim made for cryptocurrency is that it is “virtual gold”. Indeed, bitcoin was explicitly designed to echo gold, from its limited supply to its production through “mining”. So far, however, crypto has failed to provide any semblance of the stability that gives gold its reputation as a safe haven and store of value.

Gold also avoids the chief risk of CBDCs – the prospect of government interference, whether through devaluation or controls such as the time limits or purchase constraints that some expect from the digital yuan. In this light, it is worth noting that central banks continue to hold a significant proportion of their own reserves in gold.

Indeed, you could argue the entire history of currency is an attempt to replicate the advantages of gold without its drawbacks (its safety and storage requirements). As the chart above indicates, this attempt has hardly been an unqualified success. So, against an uncertain and challenging macroeconomic backdrop, and with geopolitical tensions unlikely to dissipate any time soon, gold could have a renewed role to play in investors’ portfolios.

Finally, as the chart below shows, strategies that switch between gold and government bonds might have even more to offer.

Chart 3: A strategy switching between bonds and gold delivers superior returns

The China complex

The China complex

This special edition of Panorama is dedicated to China and offers a richer way of looking at it from the geopolitical, sustainable, economic and market lenses.

About the author

-

Barry Gill

Head of Investments

Barry Gill, Head of Investments at UBS Asset Management since Nov. 2019. Previously, he was Head of Active Equities at UBS AM. Barry joined O'Connor in 2012, overseeing long/short strategy. Prior to that, he led UBS IB's Fundamental Investment Group (Americas). In 2000, Barry relocated to the US, rebuilding Equities' long/short efforts post-O'Connor. He held leadership roles in London, including co-heading Pan-European Sector Trading. Barry started his career as a graduate trainee at SBC in '95.

Make an inquiry

Fill in an inquiry form and leave your details – we’ll be back in touch.

Introducing our leadership team

Meet the members of the team responsible for UBS Asset Management’s strategic direction.