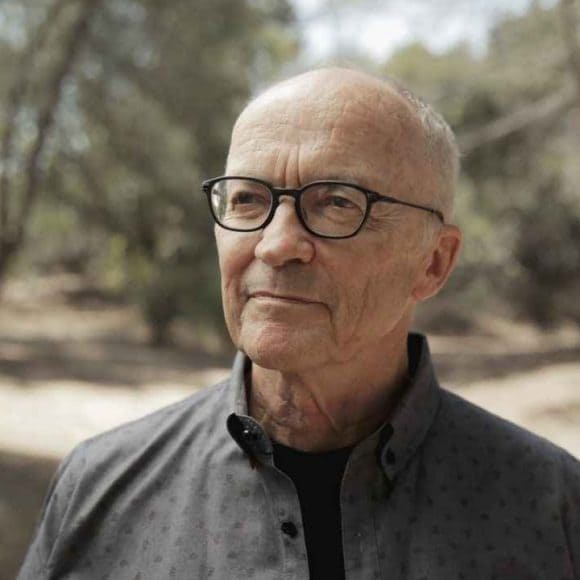

Who is Finn E. Kydland?

Who is Finn E. Kydland?

Finn E. Kydland is a Professor of Economics whose research has fundamentally shaped modern macroeconomic policy. His groundbreaking work on time consistency of economic policy and the driving forces behind business cycles, developed in collaboration with Edward C. Prescott, transformed how governments and central banks approach monetary and fiscal policy. Their research demonstrated why policymakers struggle to maintain long-term commitments and how real economic shocks—rather than purely monetary factors—drive business cycle fluctuations.

In 2004, Kydland was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, shared with Edward C. Prescott, for their contributions to dynamic macroeconomics: the time consistency of economic policy and the driving forces behind business cycles. Their work provided the theoretical foundation for central bank independence and continues to influence economic policy design worldwide.