Conversation with Kevin Zhao — Inflation, post pandemic recovery or longer-term trend?

Inflation is accelerating in the US and other major economies. But is it a temporary reflection of the post-pandemic recovery or the beginning of a longer-term trend?

Where do you stand on the great inflation debate? Are the current rates of high inflation likely to be transient or secular?

Where do you stand on the great inflation debate? Are the current rates of high inflation likely to be transient or secular?

That’s the debate among economists, market participants and even among members of the US’s rate-setting body, the Federal Open Market Committee. Although the battle lines appear to be quite firmly drawn in either camp, our view is slightly nuanced.

There is undisputable evidence that recent inflation data, by most conventional measures, is coming in stronger than expected. This can be attributed to several pandemic-related factors, such as last year’s COVID-19-induced collapse in prices, the resulting massive fiscal stimulus measures put in place to counteract deflationary demand shock, as well as supply constraints caused by the lockdown measures that put upward pressure on input costs and wages.

That said, we cannot downplay the longer-term disinflationary forces that existed prior to the onset of the pandemic. Among these are advances in information technology, a rapidly ageing population, globalization, and more recently, a sharp increase in government debt that has been historically associated with low potential future growth even if it provides a short-term boost.

Kevin Zhao is the lead portfolio manager on all active Global Sovereign and Flexible Fixed Income Strategies as well as Active Currency Management.

Disinflationary forces

When is inflation merely transitory? When does it cease to become transitory? My view is that if the above structural disinflationary forces remain intact, an output gap still exists and long-term average inflation forecasts remain comfortably and consistently close to the central bank’s 2% target, it will be premature to declare a regime change to secular high inflation.

I strongly disagree with those who have extrapolated a recent jump in the Michigan survey of consumer inflation expectations and the ten-year high of market-based break-even inflation as further evidence that the Fed is behind the curve and will lose control of price stability. The fact is, most surveys of inflation expectations or measures of market-implied inflation are ex-post and therefore reactive to short-term movement in highly-visible commodity prices. They have very limited predictive power unless backed by a material rise in wage formation and longer-term average inflation.

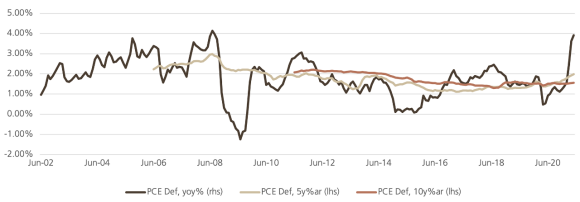

The chart below shows the PCE deflator, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, over three periods: year-on-year, 5 year and 10 year. It is evident that despite the short-term spike in annual inflation we are witnessing today, longer-term measures remain well below the Fed’s 2% target. Therefore, I believe that successful anchoring of long-term inflation expectations and structural forces are more powerful and predictive of future inflation than short-term changes in commodity prices or year-on-year price changes.

US inflation-PCE deflator

As a student of history, I am guided by the experiences of Japan and the Eurozone, where inflation expectations became unanchored after their respective central banks allowed realized average inflation to fall below 1%.

The next three years represent a golden opportunity and likely a final chance for the Fed to maintain its inflation credibility, a feat the Bank of Japan failed to achieve in the 1990s and the European Central Bank (ECB) fell short of post the Great Financial Crises. In the case of the ECB this occurred twice, the first in 2008 after it prematurely hiked rates in response to a short-lived increase in prices and again in 2012 when it overestimated the strength and persistence of the rebound in growth and inflation the prior year.

Keeping an open mind

To summarize, whether the high inflation prints we are seeing are a passing fancy or the real deal remains to be seen. I caution against drawing any firm or premature conclusions on future trends based on what we are presently witnessing in high frequency data. We should be guided by both structural analysis and empirical data learning from the experiences of others. While I agree with the Fed’s view that the current increase in inflation is transitory, I am keeping an open mind and keenly monitoring developments in terms of long-term data.

How are you implementing your views in your global bond portfolios?

How are you implementing your views in your global bond portfolios?

We have been seeking to take advantage of the recent elevated levels of volatility, particularly in rate markets. We cut the overall duration of our global strategies to the lowest aggregate duration exposure we have had since mid-2018. This move was focused on two main markets, the US and China. In the US, our view is that although yields are likely to generally move higher over the medium-to-long term, they will probably be largely rangebound in the short term as market sentiment oscillates between over-reaction and under-reaction to data releases and comments by members of the FOMC. Regarding China, it has been both a great diversifier in times of stress and a source of high-quality carry. Our decision to shorten duration emanated from concerns over possible central bank tightening in the second half of the year.

Within inflation-linked securities, we closed our allocation to US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) that we considered to have become less attractively valued. We maintain our allocation to inflation-linked bonds in New Zealand where break-even inflation is still below the central bank’s 2% target. Finally, we have an allocation to inflation-linked bonds in Japan where we consider the risk-reward ratio to be skewed positively due to higher goods inflation globally.