Bond Bites Bears come out of hibernation, but is it too soon?

Bond markets have started 2021 with a move higher in yields so what are the bearish arguments today for the outlook for bonds?

To wish readers a Happy New Year would be the normal salutation opening a January letter. But for those in the UK now enduring a third lockdown there seems little ‘happy’ or ‘new’ to the start of 2021. In the UK (and well beyond) hopes for an easy transition back to a life more ordinary have faded rather quickly. Like a central bank with an inflation target, the goal is one thing, but getting there is quite another. At least financial markets have provided the New Year celebratory fireworks largely absent elsewhere.

In 2020 the global pandemic and the monetary and fiscal policy response dominated the price action in bond markets. Whatever the long-term impact may be, in 2020 the result was emphatically positive for investors. The Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index, a broad universe of bonds tracked by many investors, returned 5.58%0 making it one of the better years for investors after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09. Bond prices move inversely to yields so a key driver was the collapse in bond yields; from 1.45%1 on the Global Aggregate Index at the start of 2020 to just 0.83%1 by year end.

2021 has begun with growing optimism in the so-called 'reflation trade'; the hope for a strong cyclical upswing and across the board expansion in the global economy. This belief is powered by several factors, not least the vaccine roll-out and an expected explosive release of pent up consumer spending, all supported by easy monetary and fiscal conditions. Nowhere is the narrative more compelling, and having a greater impact on markets, than in the US where it has been further supported by the Democrats success in the Georgia run-off elections. This has heightened belief that an even larger fiscal expansion is now possible.

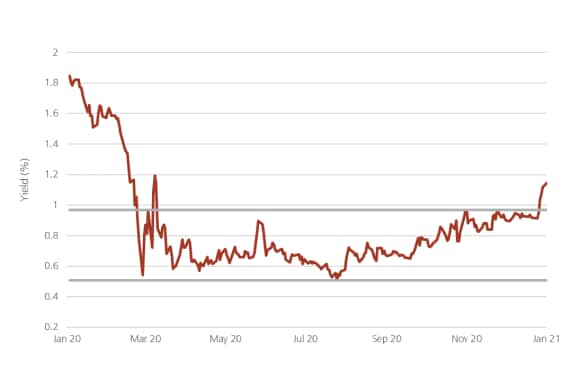

For bond markets this has led to some fairly typical early cycle reactions, a move higher in yields and fall in prices. In the US, ten-year yields have risen by about 25 bps since early December. The yield has also broken above the psychologically important level for some investors of 1%. In reality there is nothing at all significant about 1%, other than this is the first time US ten-year yields have traded outside a range of about 0.5%-0.9% since the full effects of the pandemic became clear.

US 10-year Treasury yield in 2020/21

US 10-year Treasury yield in 2020/21

The question now is whether recent events, and the assumed recovery from the pandemic, will be enough to finally end the near forty year bull market in bonds? Nobody can be completely sure today but, if this is to be the end of the bond bull market, then that will require not just a cyclical rebound but a reversal in the structural forces that have driven bond yields lower over time. After all, Chart 2 highlights that there have been many short-lived cyclical rebounds in yields but the overall structural trend lower has been incredibly durable.

US 10-year Treasury yield since 1965

US 10-year Treasury yield since 1965

What are the bearish arguments for bonds today and how should we think about them?

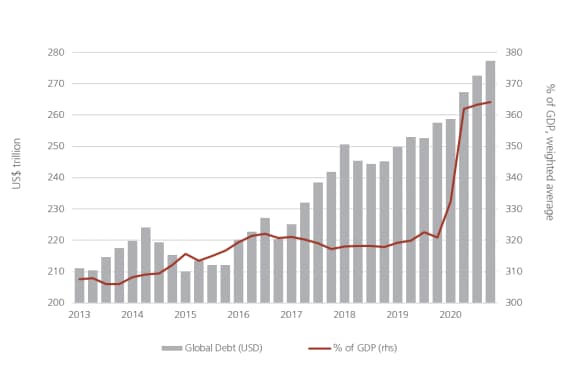

Supply; For some commentators the sheer volume of debt issuance to come, especially from governments, will be enough to cause severe indigestion in markets. And it is an argument that is intuitively appealing; after all, we know most real world situations where more supply means lower prices (all else being equal). The problem with this argument today is that, for debt, all the evidence points exactly the other way. Chart 3 highlights the dramatic expansion of global debt levels both in absolute levels and relative to global output (this data is across government, corporates and households and developed and emerging markets)2.

Global debt in absolute and relative to GDP levels

Global debt in absolute and relative to GDP levels

But we know that over time, central bank policy rates and bond yields more broadly have fallen in the face of rising debt levels (as chart 2 displays). So for those advocating a bearish stance on bonds, based on a looming supply argument, this actually goes in the face of empirical evidence which shows the opposite relationship– rising debt levels imply lower yields. If the expectation of supply alone is driving bond yields higher then the effect is likely to be very short lived.

Central bank intervention; The recent rise in bond yields might also be justified if optimism for 2021 implies a move higher in central bank policy rates, or less quantitative easing. But in reality there is no prospect of central bank policy tightening this year in most markets. To take the US again as an example, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has been at pains to guide markets not to expect rate hikes until after 2023 – even upgrading their inflation management framework last year to make rate hikes less likely in 2021 than they would have been in prior years3. And today central banks are generally active in managing yields across the curve. It is doubtful the Fed would tolerate a sustained move higher in long dated yields for fear that higher funding costs would derail the recovery. As recently as December the Fed confirmed that its asset purchases would be maintained at USD 120 billion per month "until there has been substantial4 further progress towards the Committee's maximum employment and price stability goals"4. If required, asset purchases can easily be shifted to keep yields capped at any point along the curve. So again, bond bears expecting the recovery to trigger a policy reversal are likely to be disappointed.

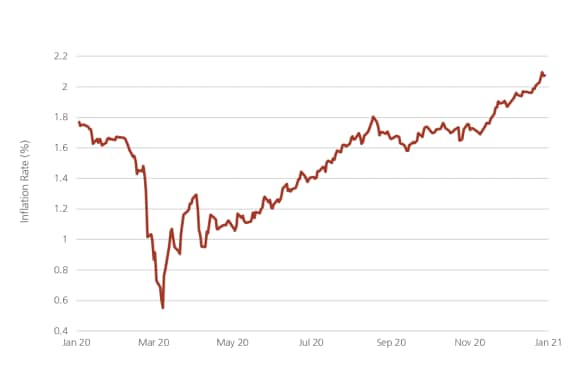

Inflation; It is also possible that the move higher in yields reflects worries about inflation. This is certainly a legitimate concern if the expected expansion in consumer spending and corporate investment later in 2021 hits supply shortages in goods and services. Although realized inflation is currently running well below the Fed's target, some market pricing of forward-looking inflation instruments have increased recently. For instance, chart 4 shows so called 'break-even inflation' for 10-year US government bonds – in effect, the market pricing of expected average inflation over the next 10 years. It is noticeable that it has increased sharply from very low levels in the summer and has touched 2% for the first time since 20185. So clearly rising inflation is a concern that is being priced in for 2021 and beyond.

US 10-year breakeven inflation rate

US 10-year breakeven inflation rate

In the light of recent events, higher US inflation expectations are reasonable in the short term; But a serious breakout to the upside in 2021 seems unlikely now given that most economies are still operating with substantial output gaps (i.e. their productive capacity is well in excess of actual output) so there is plenty of economic slack. US unemployment for instance is still running at just under 7%6, compared with under 4%6 a year ago.

At face value, this implies we are seeing only a cyclical upswing in yields similar to those that have proved relatively short lived in previous episodes in Chart 2 as excess capacity will limit the prospect for supply led inflation. And savings still run ahead of desired investment in many economies limiting upside inflation risks still further.

But bond investors must be continually on their guard. As I have argued before, aggressive fiscal policy interventions, challenges to globalization, some push back against the integration of China and others into the global supply chain and policies to reverse rising inequality may indeed be structural changes evident today that herald a secular change in the inflation outlook. If these effects gain traction in 2021 then inflation expectations and yields could start to creep higher still.

As we step optimistically, but cautiously, into 2021 then these are the cross currents we must manage. Our message though remains the same – rather than large outright directional positions on either higher or lower yields, bond investors will be better served by flexibility in approach and diversification of positions.

For more information on our recommended approach and current investment views please click here.