Introduction

Introduction

Housing is a basic need, a fundamental aspect of our lives, and an important component of economic growth. From the first mortgages, the advent of electricity and the urban industrial revolution, to the 20th century suburbia surge—housing is always evolving. A decade after the great financial crisis, the pandemic ushered in a new era. Remote work redefined the purpose of a home, introducing new migration patterns and adding to demand for home amenities. As retirement housing struggled in the pandemic’s wake, a new focus was placed on health and indoor air quality. Eventually, higher interest rates followed.

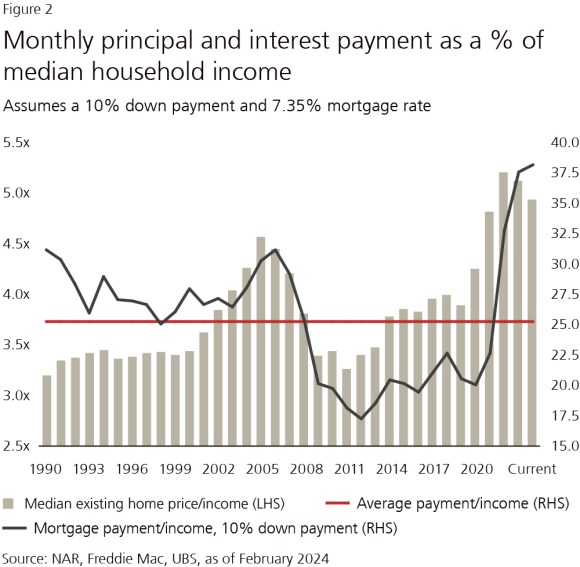

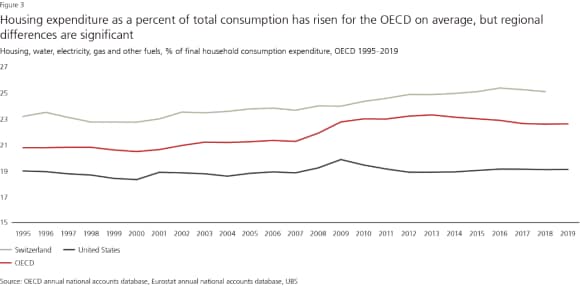

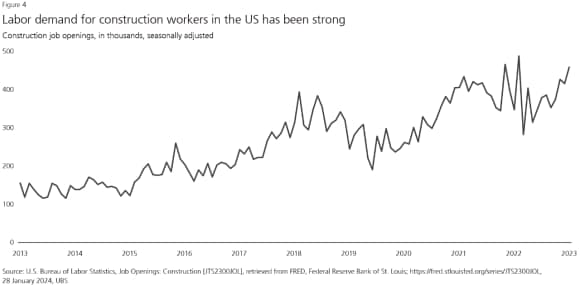

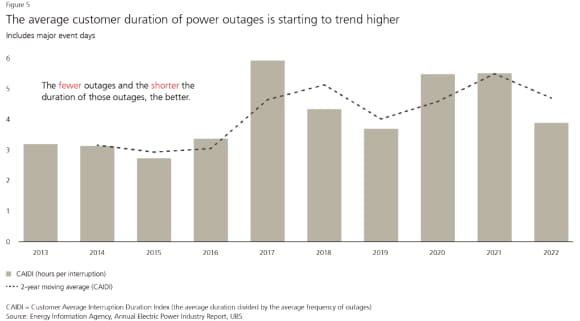

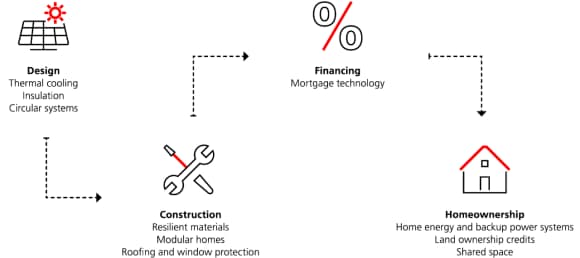

Today, as the world grapples with affordability near multi decade lows, energy security, aging, and extreme weather, what’s next? How will our homes adapt to the challenges we face? The next wave of housing innovation looks likely to center on resiliency, efficiency, and lower-cost solutions.

Housing markets are local in nature. Different regions face unique challenges and attempt to solve them with a range of policy approaches. This report does not attempt to draw one global conclusion, or predict a level of housing price appreciation over time. Instead, we address the state of the housing market, the forces shaping it for the future, and the investment opportunity across asset classes.